Career Resources

The History of Graphic Design: A Designer’s Guide

Trace the fingerprints of design giants in today’s design world.

June 12, 2025

How to Become a Freelance Filmmaker Fast

Pro tips to get from A to Z as an independent filmmaker.

June 9, 2025

Featured Articles

Must-Learn Apps for Designers & Creatives: Beginner’s Guide

What are the best apps for aspiring creatives to learn? We explore some tried-and-true and emerging software options.

Latest Posts

How to Find the Right Design Mentor for Your Career

What a great design mentorship looks like and how to become part of one.

May 19, 2025

What Is Advertising Design? A Guide for Designers

How to get ahead in advertising, by design.

May 18, 2025

30 Artists to Follow on Instagram for Inspiration

Need inspiration? We help you find good artists to follow.

April 30, 2025

Visual Storytelling Techniques That Engage Audiences

Tips and techniques for creating visuals that captivate.

April 30, 2025

15 Best AI Tools for Graphic Designers

Top tools to boost creativity, automate tasks, and streamline workflows

April 4, 2025

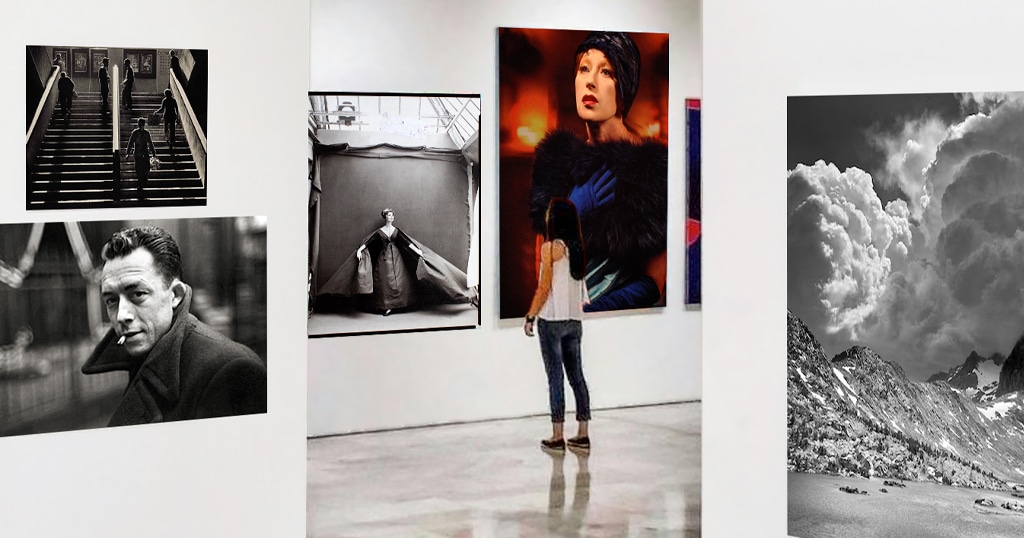

20 Most Important Photographers to Study to Improve Your Art

Our list of the essential photographers to know.

April 2, 2025

What Can You Do With a Digital Media Degree? 10 Career Paths

You have the creativity, how do you turn it into a career?

April 2, 2025

Illustration Trends 2025: What’s Upending Design This Year

Our top illustration trends to consider in your work this year.

March 30, 2025

How to Become a Creative Director

Who doesn’t want to bring a creative vision to life?

March 17, 2025

How to Make a Graphic Design Portfolio

The essential steps to put together a portfolio that attracts clients and employers.

March 5, 2025

Top UX/UI Design Tools for 2025

We survey today’s top interface design applications.

February 28, 2025

A Guide to Color Theory

Color has a way of connecting with all of us. Color theory explains why.

February 20, 2025

Here’s How to Create an Illustration Portfolio That Clients Love

Tips for showcasing your work to attract top clients.

February 19, 2025