Photography Pro Shares Her Lessons Learned on the Job

Q: Felicia, can you talk a bit about your path to becoming a photographer? What was your educational background, and what attracted you to photography as a creative career?

I had the lucky experience of growing up around cameras. My grandfather was a professional portrait/wedding photographer and my grandmother (on the other side of the family) was an avid backpacker and amateur landscape/nature photographer. When I was 14 I wanted to go to Europe on a school trip but I needed to come up with the funding all by myself.

A month or so later, I came back to my dad with the permission forms. I had raised all the money I needed by selling 8×10 prints of my photos to every person I knew! Looking back I know my photos from that time needed lots of improvement and that most of my “customers” made their purchases based on my gumption, but from that day on I had photography in my back pocket as a way to make extra cash.

Three years later I started college as a double major in Biochemistry and Forensics, on track for medical school. My first semester calculus class wiped me out, causing me to think about where I was going with my life. I switched my major to Visual Arts with a specialism in Photography and I never looked back. Now I’ve got an MFA in Photography and I love most everything about my chosen career.

Q: What important lessons did you learn in your first professional photo shoots?

I’ve had hundreds of photo shoots and I’m still learning! The biggest overall lesson I’ve learned is how to go with the flow. Shoots (and life) rarely go as planned. The true difference between an amateur and a professional is not controlling everything—it’s being prepared and knowledgeable enough to move forward when something unexpected comes up.

During one of my first weddings I remember I had just gotten a new flash and didn’t test it before the wedding. Once I arrived at the venue, I realized I could not figure out how to set it to TTL (automatic). Although I was definitely panicking, I went ahead and defaulted to the manual settings that I knew would work; it took a little extra time setting up some shots, and I had a few more bad exposures than I liked but I was able to keep on shooting.

My client never even suspected there was anything wrong. I learned a few lessons here. First, always check your gear before game time! Second, keep your composure and you’ll be able to maintain a professional impression with your client. Third, go ahead and slow down to troubleshoot if you need to, but fall back on what you know if time doesn’t allow for it.

Q: Photography requires a unique mix of creative, technical, and people skills. How would you describe the attributes to succeed in the field?

I’d say that people skills are the number one most important skill in a photographer’s toolbox. Most of my clients have already decided whether my photos are good or bad before they even leave the shoot, before they have seen what I’ve got. This is because people tend to decide whether you are a “good” photographer based on how you interact. You always want your client to leave your a shoot with the impression that you are awesome and that they are in good hands.

Having strong technical skills to back up your personality is equally important. If you are a rockstar with interpersonal relations but deliver an underwhelming product, your business will probably dry up quickly.

Try not to bite off more than you can chew, and if you do decide to take a gig that pushes your skill level, have a plan in place for how you’ll ensure a quality product and a positive impact on your reputation. This could mean hiring a lighting guru if you are new to artificial lighting or using a retouching service if your Photoshop skills are still a work in progress. Knowing when to ask for help is the key to brand management.

Q: What are some challenges of the job that any aspiring photographer should recognize?

Photography is hard work! This is a field that demands quite a lot from you; physically, emotionally, creatively. I cannot emphasize enough how important it is to set some boundaries and know your own limits. When you are starting out, especially if you are entering the field as a full time freelancer, you’ll be motivated to take every gig that comes your way. Before you know it, you’ll be sacrificing your Sunday family days, neglecting your dog for long days as an assistant, or taking work that pays far too little.

Try to keep in mind that burnout is the biggest creativity sap of all time. If you are in for the long haul, you’ve got to know when things are feeling a little too much like work and make changes to turn it back into passion.

The second largest challenge of a career in photography, or any creative or freelance job, is money. Most fields of photography have busy seasons and slow seasons, so having the ability to budget and plan accordingly is key. On top of that, you’ve got to deal with negotiating fair rates with your clients. For example, if you’ve got a restaurant manager hiring you, maybe they make $30/hour. When you come to them asking for $200/hour they are going to want to know what you’ve got that makes you such a hotshot. If you are coming off your own hourly job, you might be asking the same question. It’s important to figure out your rate and stick to it if you can.

In my case, I’ve got to pay for photostudio rent and utilities, photographer’s insurance, equipment repairs and acquisitions, subscriptions to Adobe and various other software, and more. That seemingly pricey $200/hour rate quickly drops down as you begin to deduct all the expenses I’m paying for with that rate. Factor in that I might only shoot twice a week rather than the 40 hours an hourly worker can count on, and I’ve got even less cash to play with.

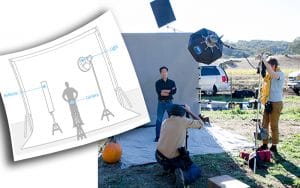

Q: In your Photo Setup course you explore the complexities of staging and lighting a photo shoot. How essential is that to creating professional work?

Attention to detail can make or break a photo, especially when working in a posed situation. Creating a scene from scratch requires a fair amount of thought and examination of the frame from edge to edge from both a creative and a logical perspective to be sure you are including the right props and other elements. You obviously want your work to make sense!

Natural light is great, and I use it every chance I get. However, in winter, when it’s dark out by 5pm, shooting during daylight hours really limits the amount of work I can take on. Having good lighting skills is also incredibly helpful for shoots like sunny, summer catalogues, which are often shot during the gloomy, grey winter before!

Q: What percentage of your time is spent doing setup versus shooting?

Sometimes, I shoot documentary style for clients. This is usually pretty great for me…I get to walk in and just do what I love: make photos! Often though, I’m spending time working out the logistics of mood, style, props, composition, delivery method and type, payment terms, and usage rights. Afterwards, I’m breaking down equipment, returning unused props, and culling, editing and retouching the images.

On a scale, the actual time spent behind the camera is fairly minimal. In general, for every full day shoot I coordinate, I’ll spend at least another full day between the pre- and post-production tasks.

Q: One thing we love about your course is that it explores professional lighting scenarios like Avedon and Rembrandt lighting. What does it take for these techniques to become second nature?

Someone said that it takes 10,000 hours to become a master of a craft. This is so true with photography. There is nothing as valuable as time and practice. Specifically, consistent, and regular practice. If you take your lights out once every six months, you’ll spend most of your time refreshing yourself on how to use them. If you take them out once a week for 2 months, you’ll have the hang of them in no time.

Q: Why is it important is it for photographers today to understand the techniques and approaches of the early masters and the major century photographers?

Nothing in the world is created in a vacuum. Today’s photography is influenced by older photography, which was influenced by painting. Understanding how your work fits into a larger context enriches what you bring to the table as a working artist. Knowledge of the old ways can also be incredibly helpful when you need to innovate your way out of bind or a creative slump.

>Q: Being a photographer is clearly a lot of work. Complete this sentence : Photography is still fun for me because ________.

Photography is still fun for me because every day I get to continually challenge myself and push the boundaries of my skill set. Each gig is a little bit unpredictable, keeping me on my toes and keeping my mind sharp. I also get a big high from seeing a client’s problem and providing an awesome solution. The ability to set my own schedule and curate clients that I’d like to work for are nice perks too. 🙂

Visit sessions.edu to find out more about Digital Photography degree and certificate programs at Sessions College. Click here to view Felicia Kieselhorst’s faculty bio or visit her website fotosbyflee.com.

Gordon Drummond is the President of a Sessions College. He's passionate about education, technology, and the arts, and likes to surround himself with talented people. Read more articles by Gordon.

RECENTLY ON CAMPUS