Design Deconstructed: Abstract Expressionism

Design Deconstructed examines which art movements influenced today’s visual culture, and why.

In the 1940s, a new form of art was beginning to take form in Lower Manhattan. On the heels of World War II, and with the Great Depression fresh in their memory, the New York School, or Abstract Expressionists, as they would come to be called, found themselves on the verge of a new America.

Following World War II, the United States was experiencing a period of rapid economic growth that stood in harsh contrast to the not-so-distant recession of the previous decade. For this new wave of artists, the social realist styles of painting that depicted the harsh realities of America’s poor and working-class were no longer reflective of their reality.

This post-war period marked an important chapter for the United States not only in terms of economic development, but also culturally. It was through Abstract Expressionism that the world’s attention would for the first time shift from the European cultural hubs like Paris, to the developing art scene in New York City.

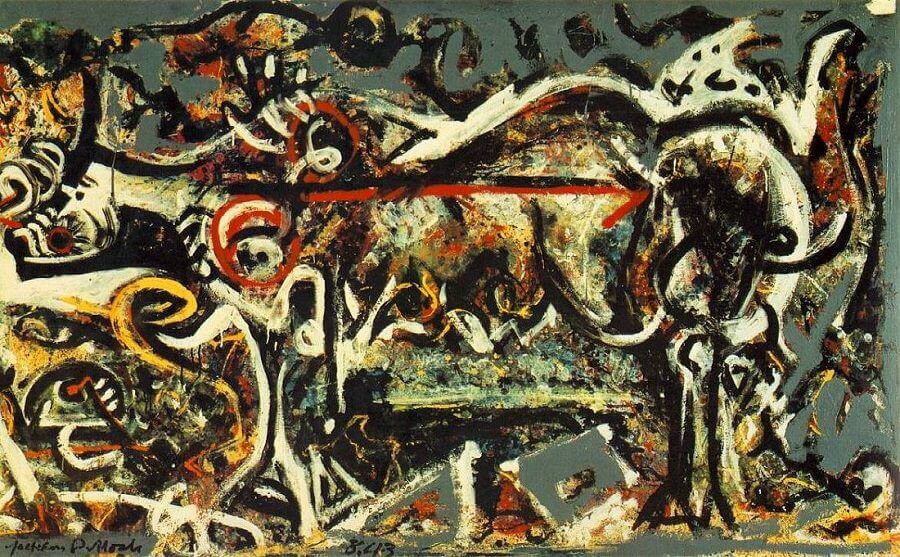

The She Wolf by Jackson Pollock, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

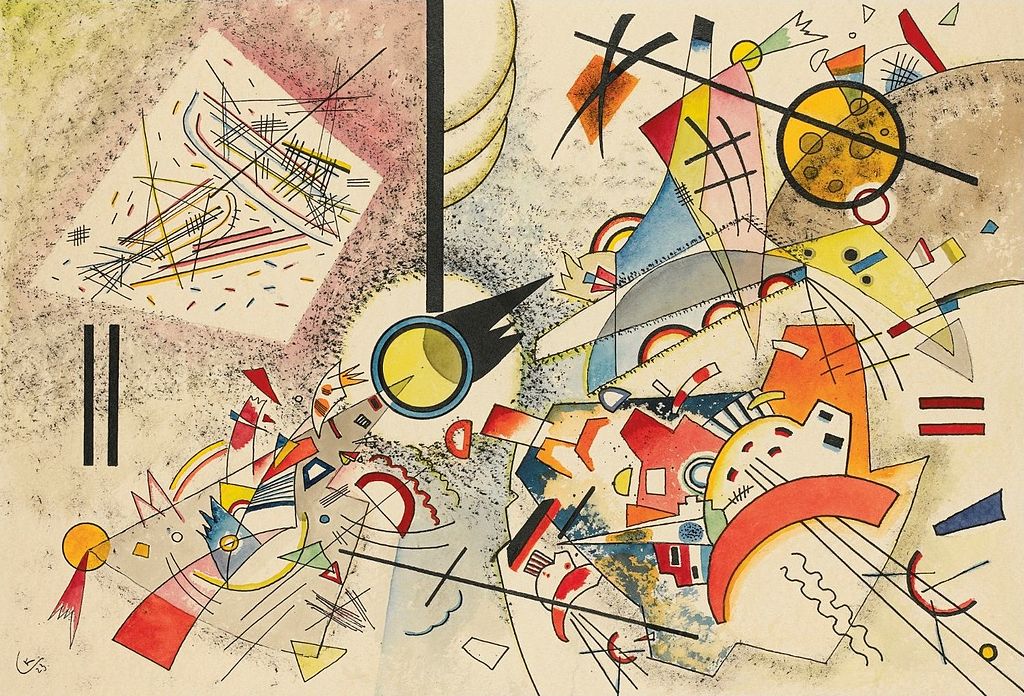

Abstract Expressionism was largely influenced by European Modernism. For years, American audiences had been exposed to European movements like Cubism, Surrealism, and Dada, through the works of artists like Picasso, Mondrian, and Kandinsky. Additionally, many artists fled from Europe during World War II and sought refuge in the United States, where they continued their practice and in some cases, became teachers.

Following in the footsteps of Modernism, Abstract Expressionism challenged convention in just about every conceivable way. The Abstract Expressionists abandoned tradition entirely, experimenting with subject, media, and scale in ways that had never before been seen.

Piet Mondrian, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Part of what makes the works from this period so recognizable is their lack of subject matter. For the Abstract Expressionists, the painter themselves became the subject, or rather, subjectivity itself became the subject. Turning their focus within, the creation of a painting became an exploration of the unconscious, with whatever resulted on the canvas serving as evidence of that journey having taken place.

Above all, Abstract Expressionists sought authenticity. As such, improvisation was seen as the best tool for tapping into the unconscious and accessing the artist’s authentic self. This line of thinking was in part inspired by practices and ideas espoused through Surrealism and the work of Carl Jung in the field of analytical psychology.

Abstract Expressionist works from this period can be categorized broadly into one of two categories, Action Painting and Color Field. While both categories shared an interest in the unconscious, it could be said that Action Painting focuses on the unconscious of the painter, while Color Field is more interested in the unconscious of the viewer.

Wassily Kandinsky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Art falling into the Action Painting camp offers a snapshot of time, a window into the psyche of the artist. Viewers gain an intimate view of the mental state of the painter at the time of the painting’s creation through the clearly evident mark-making and energy expressed through the canvas. These paintings impart a strong sense of movement, time, and gesture, allowing viewers to share in the intimacy and catharsis of the process.

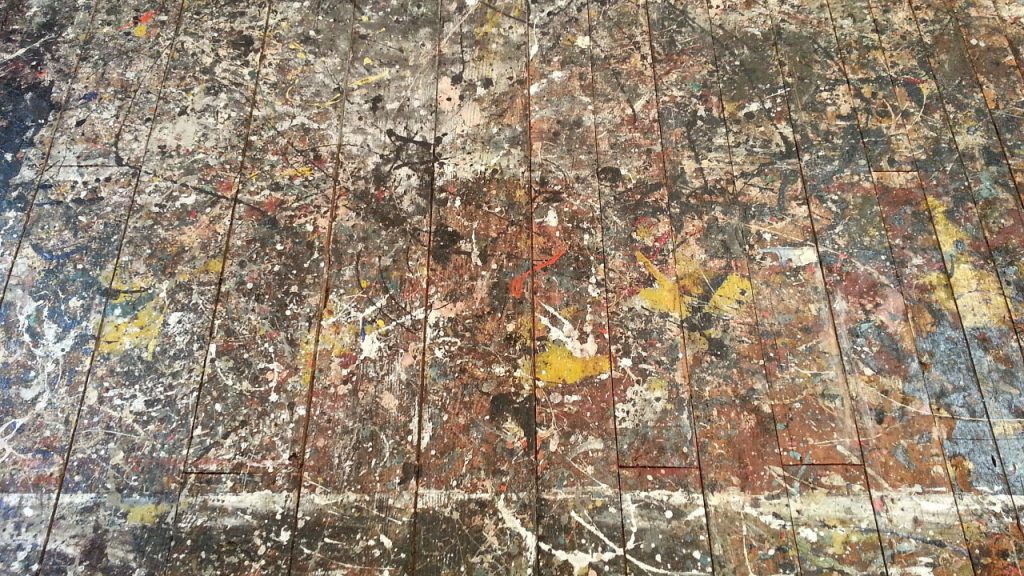

The most famous artist associated with Action Painting is Jackson Pollock. One of the first Internationally famous American artists, and perhaps one of the most unconventional as well, Pollock neither primed nor stretched his canvases, which allowed him to work at a larger scale and stand atop them as he worked. With a cigarette hanging from his mouth, Pollock would go about rhythmically flinging thinned-out paint across the canvas, slowly transforming it into a reflection of the process itself.

In contrast with the action-oriented works of artists like Pollock, the works falling into the Color Field category sought to create a more introspective experience for the viewer. Rather than achieving any measure of objective beauty on the canvas itself, the painting served as a means of creating “sublime” mental states within the viewer.

Wassily Kandinsky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

For both Action Painting and Color Field, scale played an important role in establishing a sense of intimacy. Scale and proximity were leveraged to produce emotional reactions, allowing viewers to feel as though they were being surrounded and taken in by the painting, with works by Rothko having been said to have even brought about religious experiences in viewers.

Through their attempts to tap into something within, the Abstract Expressionists managed to tap into something universal, putting America on the map artistically and making New York City a contender for the new hub of culture in the process. The at-times dynamic and reflective works from this period challenged the status quo by giving greater importance to the process rather than the outcome.

This gave birth to new styles of abstraction based on similar principles as well as movements that arose in direct opposition, like Pop Art in the 50s. Abstract Expressionism marked the beginning of an era of American cultural export, the effects of which are still felt today.

Header image source: Jackson Pollock Krasner House Studio Floor by Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Taylor is a concept artist, graphic designer, illustrator, and Design Lead at Weirdsleep, a channel for visual identity and social media content. Read more articles by Taylor.

ENROLL IN AN ONLINE PROGRAM AT SESSIONS COLLEGE: